Guide to Product Management

Having worked across a number of companies in the technology and startup universe, we find ourselves referencing the same material over and over again. The information that we find to be most useful is put together by thought leaders who have succeeded as Product Managers out in the real world. That perspective is a bit different from what you’d find in a typical Product Management course online. This outline will serve two purposes: first, it will help clients and prospective clients understand how we think about modern Product Management; second, it will help those interested in careers in Product Management scout the terrain to be traversed.

We get that every organization asks something different of its Product Management function. There are drastic differences between an early-stage startup looking for product market fit and a well-established company looking to capitalize on existing customer relationships and momentum. This material covers a broad spectrum of ideas and issues, from startup to late-stage and from B2B to B2C. These ideas and resources are no substitute for a comprehensive Product Management course, but they have been helpful to clients and learners in the past. Hopefully they will be helpful to you as well!

We’ve embedded audio and video content and linked to written content. We’ve also linked to authors’ Twitter feeds, where those authors are actively tweeting about relevant material. We have found this group of authors to be reliable sources of innovative and insightful thinking.

We’d especially love to hear about any materials you’ve discovered that you think could fit in here. Feel free to email us at hello@inroad.co!

The Guide to Product Management is organized as follows:

- What is Product Management?

- Understanding the Customer

- Understanding the Industry

- Organizing the Roadmap

- Validating Solutions

- Defining the Product

- Managing the Build

- Releasing the Product

- Advanced: Building a Product Team

- Helpful Resources and Citations

I. What is Product Management?

The “job” of a Product Manager is guiding the development of products and features to successful outcomes. How we go about defining and attaining success can be the tricky part. What looks like a success to an engineer or a designer might look different to a sales manager. The development of broad-based buy-in is just one of the many complex responsibilities Product Managers must now manage. Before jumping into a general discussion of the Product Manager’s role, it might be helpful to learn how the function we now call “Product Manager” came into being.

History of Product Management

Our choice as the best short history of the concept is The History and Evolution of Product Management, a piece by Martin Eriksson. Eriksson starts by explaining how Neil McElroy deployed “brand men” at Proctor and Gamble in 1931. Acting as an advisor at Stanford a decade later, McElroy discussed his thinking with Bill Hewlett and David Packard, who were then launching their computer electronics company. They gave Product Managers responsibility for bringing the voice of the customer into internal discussions at the company. Don’t discount the importance of understanding how the role of Product Manager has evolved to encompass a great breadth of related issues. Taking disparate factors into account in an orderly, balanced, and carefully prioritized way is one of the keys to success. Martin Eriksson is an experienced Product Manager who cofounded the blog Mind the Product (one of our favorites).

If you prefer an audio explanation, try The (Abbreviated) History Of Product Management podcast by Rocketship.fm:

So... What is Product Management?

Ok, now back to the original question. We think Martin does an excellent job of defining the current state of the field in his post What Exactly is a Product Manager?. Another good outline of Product Management responsibilities is available from The Product Podcast, a project of Product School. Their “What is Product Management?” podcast explains what Product Management is (and is not):

The Product Lifecycle

Now that we have a good general understanding of the Product Manager’s job, let’s look at some of key strategies successful Product Managers employ to help their teams hit important goals. This post, Great PMs don’t spend their time on solutions by Intercom (a B2B messaging apps company) talks at length about The Product Lifecycle and where Product Managers should spend their time. An important takeaway here is that great Product Managers have a deep understanding of the problems that they’re trying to solve before they ever start thinking about solutions. We’ll talk about this a bit more in the next section.

Good vs Great Product Management

When we say great PMs have a deep understanding of the problem, we’re serious. Before they even start trying to come up with a solution, great Product Managers make sure they understand the customer’s needs from the customer’s point of view. Let’s be clear that the customer’s point of view can include a lot things that don’t fit conveniently into spreadsheets. Only by understanding the customer and their situation in depth can we position ourselves to help in the optimal way.

Good Product Manager / Bad Product Manager by Ben Horowitz is a post that is constantly referenced by accomplished Product Managers, particularly in the startup community. Ben founded and ran the enterprise software company, Opsware, before founding and running the venture capital firm, Andreeson Horowitz. Ben prefaces this blog post with a warning, “This document was written 15 years ago and is probably not relevant for today’s product managers. I present it here merely as an example of a useful training document.” It holds up and is definitely worth reading.

Great Product Managers think about achieving outcomes vs building features. We don’t want to give the user the gizmo they think they want. We want to help them accomplish a goal. With this mindset, both the Product Manager and the organization at large are more likely to understand whether or not products are actually achieving the right goals (the goals of the user, understood from the user’s point of view). Max Bennett does an excellent job of explaining this distinction in his post Great Product Managers are “Outcome Thinkers”.

Ian McAllister provides a helpful take on this question on Quora in his answer to What distinguishes the Top 1% of product managers from the Top 10%?. Based on his experience as a Product Manager at Microsoft, Amazon, and Airbnb, Ian is well-equipped to answer the question.

We don’t think an MBA is a requirement for great Product Management, but publications like the Harvard Business Review have been helpful. What It Takes to Become a Great Product Manager by Julia Austin is one such resource. Julia is a Senior Lecturer focused on entrepreneurship at the Harvard Business School. She has deep experience both on the operating and on the advising side. We’re including this article because it looks beyond core competencies, instead looking at EQ and company fit.

Great Product Managers are willing to take great calculated risks – especially when the pace of growth and/or other contextual factors favor risk. In his talk “10x Not 10% : Product Management by Orders of Magnitude” Ken Norton, Product Manager and Senior Operating Partner at Google Ventures, talks about how Product Managers should fight their instinct for loss aversion and go for moonshots:

If you’d like to go deeper into understanding what excellent Product Managers look like, check out: Behind Every Great Product Manager by Marty Caagan, What is Product Management by Roman Pichler, and Product Manager Skills By Seniority Level — A Deep Breakdown by Brent Tworetzky.

II. Understanding the Customer

Products are solutions. Before you can develop a smart solution, you need a complete understanding of the problem or opportunity. In the case of a business, customers are paying you (in one form or another) to solve their problems. They may pay you to solve problems they don’t know they have (before the iPhone, lack of 24X7 portable access to email would not have been considered a problem). It’s important to remember that your customers are people, who may not view problems and solutions in purely objective, rational ways (assuming you’re reading this before the robots take over).

We recognize that there are likely going to be multiple customers (stakeholders) that the Product Team should be concerned with – including internal stakeholders – but for the purpose of this guide, we’ll focus on the end users. Ultimately these are the customers we’re trying to serve.

Customers First

Understanding your customers on a “personal” level is probably the most important skill that a product manager can have. As Amazon states in their Leadership Principles, “Leaders start with the customer and work backwards. They work vigorously to earn and keep customer trust. Although leaders pay attention to competitors, they obsess over customers.” If you read that list in full, you’ll notice that this is the first of Amazon’s fourteen leadership principles. It’s important.

We’d be remiss if we didn’t have at least one piece of content here from the great Steve Jobs. This video is from Apple’s 1997 Worldwide Developer Conference. In it, Steve Jobs explains to a disgruntled developer why it’s important to start with the customer and not with the technology:

Obsessive focus on the customer experience is the basis for the Product Management discipline called Design Thinking, a school of thinking popular enough, and effective enough, to warrant the creation of training curricula at universities like MIT and Stanford.

The Product School offers a concise explanation in Design Thinking in Product Management. Another good introduction is Design Thinkng, Explained from MIT’s Sloan School. For a little practice in staying flexible with your point of view, check out The Octopus, from IDEO, the design firm that launched Design Thinking as a Product Management discipline. If you want to know more about the roots of Design Thinking, check out Design Thinking,Tim Brown’s seminal article in the Harvard Business Review.

Collecting Information

There’s a lot of great information out there on user research, but we think the article The Product Manager Superpower: User Science does a nice job of laying out what different customer touch points might look like, and how to incorporate user-centric information back into your company’s programs.

One important note that you may get, in a B2B company in particular, is distinguishing between users and buyers. As a Product Manager your job is not to build for buyers. This article in HBR explains why.

Getting organized in regard to feedback should be a top priority task for any Product Manager starting a new project. Veteran Product Manager (Linkedin, Microsoft) and successful entrepreneur Sachin Rekhi offers suggestions in his blog post about Designing Your Product’s Continuous Feedback Loop.

Jobs to be Done

Harvard professor Theodore Levitt is often quoted as saying, “People don’t want to buy a quarter-inch drill, they want a quarter-inch hole.” We think this quote perfectly distills down the idea of “Jobs to be done,” one very popular and successful approach to analyzing the customer experience. What was the “job to be done” that customer’s associated with the cell phone? We now know it wasn’t making telephone calls. It was communicating. Successful Product Management requires thorough understanding of this principle.

The person who popularized this idea is another Harvard Professor named Clayton Christensen. Here, Clayton explains his synthesis of jobs to be done:

For a bit more information on this, see Clayton Christensen’s post in HBR Know Your Customers’ “Jobs to Be Done”. HBR also put out a helpful podcast on the topic:

Fundamentally, we want consumers to “hire” our product to do a job for them. To fully understand what might motivate them to do so, we need to understand each and every step the consumer goes through in completing that job and understand what the customer needs at every step. Tony Ulwick defines “customer outcomes” and breaks down how to solicit them in his article Turn Customer Input into Innovation.

Traditional Customer Segmentation

Paul Graham, founder of Y-Combinator, once said ““It’s better to have 100 people that love you than a million people that just sort of like you. Find 100 people that love you.” As a Product Manager, it’s not your job to make every possible customer happy. It is your job to have a deep understanding of the customers whose problems your product will aim to solve.

There are a number of different ways you can segment a customer base. It will pay to do some homework on the pros and cons of different approaches. The 6 Types of User Segmentation and What They Mean for Your Product does a very good job of explaining some of the traditional ways businesses segment customers. These methods can come in handy from time to time, but we think there’s a better way of segmenting users around what they actually need from the products you might build. That’s next.

Jobs-driven Segmentation (New Products)

Suppose we look at the challenge of segmentation and targeting from the perspective of jobs-to-be-done. How does this affect how we segment users? The post Market Segmentation Through a Jobs to Be Done Lens, also by Tony Ulwick, is enlightening.. Here, Tony explains why traditional methods of market segmentation are often ineffective.

Tony also offers a helpful case study on use of his frameworks through his consulting company, Strategyn. A deep dive on the “segmentation” element of this framework starts at 18:30:

It’s interesting to note here that jobs to be done and traditional segmentation dimensions are compatible. In our estimation, you need to understand not only the tasks that users will want to complete, and their motivations for completing those tasks, but who the users are beyond those tasks, if you want to develop a holistic view of the problem you’re trying to solve. Page Laubheimer does an excellent job of explaining this in her article Personas vs. Jobs-to-Be-Done. For an explanation of how personas can be helpful for Product Managers, see Personas Make Users Memorable for Product Team Members also from the Nielsen Norman Group.

Still curious? For a deeper understanding of some of these concepts, we’d recommend reading Tony’s book, What Customers Want. The book maps out exactly how to use customer input to drive innovative Product decisions.

The Technology Adoption Life Cycle

We now have our target customer segments, which are informed by their “jobs to be done.” Before moving on, we think it’s also important to understand where these customers fall on the Technology Adoption Life Cycle spectrum. For an overview of this important topic, check out this video:

Ultimately, customers at different stages of this cycle have different expectations of products. Before deciding what solutions might be appropriate for these customers, we need to understand where our product stands in relation to these expectations. If our product is brand new, and we’re trying to win over the first few innovative thinkers, that’s one thing. If the product has earned acceptance among innovators and early adopters, and we now seek to break out into the larger market, we need to think a bit differently.

The “bible” on this topic is Crossing the Chasm by Geoffrey Moore.

III. Understanding the Business

Let’s say we understand the customers we’re targeting, what jobs they are ultimately going to hire a product to do, how they expect to get the job done, and a bit about their attitudes toward change and innovation. As a Product Manager, you probably work within the confines of a broader company. That company probably has a perspective on the value it’s trying to provide to customers. That perspective may well be reflected in a mission statement that carries a lot of weight within the company. If you’re working for a startup, thinking of this sort may be more fluid, or what’s sometimes referred to as an emergent strategy (not “top down,” not explicit). In any event we must take care to assure that our progress toward a good solution for customers is synced with overarching goals and values of the company. We’re going to keep this section fairly high level, so that it’s applicable across roles and companies; but rest assured the links provided will facilitate a deeper exploration of the relationship between business strategy and Product Management.

The Company Mission

Everyone at the company should have a good understanding of the mission, but this is especially true of Product Managers. That’s why Product Managers should be ever mindful of the company’s mission, as kind of a “north star” that guides product development. This TED talk by Simon Sinek does a pretty good job of explaining what makes an inspiring company mission:

Here are some other good examples of mission statements across companies. The quality of your company’s mission statement is not the issue. The issue is whether your strategy for the development of the product aligns with the company’s strategy for its long-term development and growth.

Company Strategy

Many of these sections could be courses unto themselves. That’s especially true of this section. Entire MBA programs revolve around equipping executives to become masters of strategic thinking. The term “strategy” can also be pretty abstract. The key point here is that mission is one thing, strategy is another. Putting a man on the moon is a mission. Dividing the engineering challenges into a dozen or so manageable pieces (as opposed to one or two unmanageable ones) is a strategy. In his HBR article, Demystifying Strategy, HBS professor Michael Watkins describes strategy as “a set of guiding principles that, when communicated and adopted in the organization, generates a desired pattern of decision making.

A strategy is therefore about how people throughout the organization should make decisions and allocate resources in order accomplish key objectives. A good strategy provides a set of guiding principles or rules. The principles or rules define the kinds of actions people in the business should take (and not take) and the kinds of things they should prioritize (and not prioritize) to achieve desired goals.”

The decisions you make regarding Product Development –not only what to build but how / when to build it – ultimately must align with the business’s strategy. Any significant misalignment is a liability. WTF is Strategy by Vince Law does an excellent job of explaining how a company’s mission informs strategy, which informs roadmap, etc.

As a bonus here, we’ll direct you to Facebook VP Julie Zhao’s post entitled How to be Strategic. In it she explains what a successfully implemented strategy actually looks like out in the wild.

Product Strategy

Product Strategy is the part of the overall business strategy that you, as a Product Manager, can control. Within the realm of Product Strategy, we’re seeking to marry what’s being asked of us within the company strategy to the problems we know our customers are trying to solve on the ground. For some interesting insights on bridging this gap, listen to a talk given at TNW 2016 by the previously mentioned Julie Zhao, “Building with Creative Confidence”:

Oftentimes, your Product Strategy will take shape as a roadmap. As we’ll explain next, a “roadmap” can take many forms. Finding the form that’s right for you and your company will be a huge help.

IV. Organizing the Roadmap

At this point, we understand the customer, the business, and the strategy (to the extent one exists). The next step is distilling all that information down into the actual product roadmap. The roadmap should take into account important contingencies, dependencies, and constraints. In the category of constraints, scarcity of developers is likely to be important; consequently, you’ll need to be judicious about what you build and when. Your completed product roadmap is the document that defines the action plan. Before we jump into the process of building a roadmap, we think it makes sense to first explain what a roadmap shouldn’t be: 12 Signs You’re Working in a Feature Factory.

Roadmap Definition

A roadmap should not be a listing of the features and dates you hope to ship in the coming months, quarters, even years. Rather, a roadmap should communicate your product strategy in context. Check out this talk by C. Todd Lombardo, VP of Product at Machine Metrics, which elaborates on how roadmaps relate to elements of the company mission and strategy:

We also like this post by Heather McCloskey, where she talks about Outcome-driven Roadmapping. In Heather’s view, we want to take the user outcomes that we’ve collected to this point and group them into themes. Themes will be sets of outcomes that generally relate to the same overall goal. Thinking about themes can help us understand how features will relate to each other once released.

OKRs

Within our discussions with design and development teams, Product Managers should not be prescriptive about what the solution looks like. That will ultimately be designed by the broader team. On that score, let’s just say two heads, or three, or ten, are way better than one. However, Product Managers should be prescriptive about the objective for solutions. Product Managers can benefit by doing some thinking within the framework of OKRs (objectives and key results). The OKR concept goes back to Andy Grove and his success as CEO of Intel. If you’re not familiar with OKRs, check out this post by Rick Klau, Senior Operating Partner at Google Ventures, entitled How Google sets goals: OKRs.

In a Product context, OKRs take on a more specific meaning. Julie Zhuo breaks this out in her article How do you set metrics?. If you’re looking for examples of helpful metrics for startups, look no further than Dave Mcclure’s Pirate Metrics.

At this point you may ask, “I already have all of these outcomes that my users are trying to achieve, can I just use those as my OKRs?” The answer is “yes,” BUT . . . make sure those outcomes are measurable and adhere to the guidelines set out above. Above all, we need to avoid substituting outcomes that seem desirable from our own subjective point for those sought by the customer and, in the big picture, by the company.

If you want to take a deeper dive on OKRs, how to set them and what makes them effective, we’d recommend checking out the book Measure What Matters, written by John Doerr, the chairmen of venture capital firm, Kliener Perkins.

Prioritization

Say we have a list of all the things our product could potentially accomplish. That’s great. But what if it’s a long list? In that case, we need to order the list by priority. As stated in Product Prioritization by the Numbers, different organizations approach prioritization differently. Sometimes making this call is up to the Product Manager and sometimes it’s not.

As a first step, form your own perspective as to whether or not the decision ultimately falls to you. If you think it does, or should, prepare. There are a number of different approaches you can use, but they all boil down to a simple determination: which products or features will have the highest return on investment for the company?

Folding Burritos offers a number of helpful resources on Product Management, one of which is their semi-exhaustive list of prioritization models in 20 Product Prioritization Techniques: A Map and Guided Tour.

You should also check out this podcast from The Product School:

We’re not going to say definitively that there’s one ideal way to prioritize a backlog of features or possibilities, but if you’re looking for a simple approach to this challenge, check out Ian McAllister, Director of Product at Amazon, in his Quora answer to the question What are the best ways to prioritize a list of product features?.

Keep in mind that ROI calculations should account for opportunity costs associated with NOT fixing product bugs / issues. Check out the post Juggling Priorities to see some options for incorporating bugs into the prioritization equation.

One final note on the use of prioritization comes from Ken Norton in his post, Babe Ruth and Feature Lists, where he talks about certain misunderstandings you can engender in the structure of your roadmap.

Saying "No"

Inevitably, there will be a number of opportunities that don’t make the roadmap. Also inevitably, a large number of these opportunities will be product requests from inside your own company. As a Product Manager, you need to be able to maintain lines of communication and feedback loops throughout the organization. That means you need to be diplomatic about how and why you say “no.” Any decision that threatens to disrupt an important relationship must be considered and handled with great care. This post, entitled Negotiate like a pro: how to say ‘No’ to product feature requests does an excellent job of explaining how to say no constructively.

V. Validating Solutions

To this point, we’ve done no thinking about the actual “solutions.” So, we are on the right track. As Albert Einstein once said, “If I had only one hour to save the world, I would spend fifty-five minutes defining the problem, and only five minutes finding the solution.” That Product Managers need to approach their work similarly is a point that bears emphasis. The best Product Managers go deep on the problem before they even start thinking about how to solve it. Before we move ahead on this front, check out this talk from Michael Sippey, a former VP of Product at Twitter now at Medium:

Let’s understand that solutions-oriented thinking is seductive. As you start to put some of the skills we’re discussing into practice, you’ll be tempted to bring some “solutions thinking” forward in the process. You’ll want to start brainstorming solutions before developing a thorough understanding of the problem space. Our advice is, avoid this temptation – particularly in conversations you have with users. Don’t cloud their perspective and input with your own ideas about how their problems should be solved. If you’re asking yourself whether you’re ready to move on to the solution, relax, you probably aren’t. That being said, the day will come when we enter the “solution space” of the Product Management Process.

The Opportunity Solutions Tree

If you are curious about the process of fitting together ideas around customer input, outcomes (OKRs), and opportunities, there’s a relatively new “framework” that seems practical to us called the Opportunity Solutions Tree. It was developed by Teresa Torres, who is an expert in Product Discovery. For an excellent overview of her take on Product Discovery and how it relates to some of the formative work in the Product space, watch her keynote from Productized Conference 2016 in Lisbon:

For a bit of a deeper dive on the framework, and a supporting podcast, see An Introduction to Modern Product Discovery.

Generating Solutions

Okay, so, more concretely, how do we go about finding elegant solutions to customer problems? You guessed it – brainstorming! For digital solutions, you’ll want a group that includes both a UX designer and an engineering leader. Broadly speaking, the more folks you involve in the brainstorming process, even at the risk of creating a bit of short-term chaos. Different organizations have different ways of managing brainstorming sessions, and there is no bible on this subject, that we’re aware of, but we have a lot of confidence in this guidance from University of Pennsylvania Organizational Psychologist, Adam Grant:

If you’re looking for more on how to think about brainstorming solutions, check out these articles from HBR and McKinsey.

Testing Solutions

Serious as we may be about focusing on the customer, and designing around the customer’s experience, we must never assume that solutions developed in this way will make the customer happy. The solution we have in mind may bring with it a new set of problems. The more testing we can do, and the sooner we can do it, the better off we are going to be. Ideally, if we’re off base in any way, we’d like to learn that before our team has written a single line of code. That’s why a lot of successful Product Managers rely on paper prototypes of one sort or another. Paper prototypes bring the customer experience to life quickly and economically. They allow us to experiment at low cost.

If you’re not familiar with paper prototyping, here’s a quick and easy video intro from Todd Hausman, a UX researcher at Google, Melissa Powel, a program manager there, and Mariam Shaikh, a UX designer there. This video is the first in a series of three videos covering the subject of prototyping more broadly.

Different business aims warrant different approaches to experimentation. A new iteration of an established product is one thing. An entirely new product – to be introduced by a startup – is another. As a startup, you’re trying to validate much more than the product. You’re trying to validate the basic appeal of the idea, the market for the product, and oftentimes the business model itself. The scope of those challenges frequently calls for the development of a minimum viable product, as opposed to more narrowly focused experiments

Experiment Design

Prototypes and experiments will be most productive when the underlying methodology is logical and evidence-based. If you have a background in Science (or took a science class back in the day), you’re probably familiar with The Scientific Method. We think the Scientific Method provides a pretty good framework for thinking about product experimentation. Check out this talk by a Ruben Lozano, Google PM, at ProductCon Seattle 2019, where Lozano talks about applying the Scientific Method to product experimentation:

Also, we really like this post from Simon Cast at Mind the Product, entitled Everything a product manager needs to know about experiments. In it, Simon breaks out how experiments should be designed, how to incorporate results back into your company, and some tools to use that may be helpful. Ideally, our experiment is going to validate a hypothesis that relates to moving the needle on our product’s OKR by some amount. It’s not always easy to get that kind of result in an experiment, so take your time and try to think creatively about an experimental hypothesis that can serve as a fair proxy for your product objective.

Bear in mind that there are different types of experiments at your disposal. In the post What Type of Lean Startup Experiment Should I Run?, Innovation Coach, Tristan Kromer, breaks down some of the more important types and discusses when to use each.

The process of experimentation, trial, feedback, and iteration should be continuous. If at first you don’t succeed, that’s normal. Companies like Optimizely specialize in testing / experimentation and have published excellent posts like this one, entitled Experiment, Launch, Iterate, Repeat: Why Product Development is Never Complete. You can never be 100% sure you’re building exactly the right product, but you can be sure that each loop through the iterative process is increasing your chances very significantly.

For an explanation of what this type of experimentation could look like at an established company, we recommend checking out the book Sprint written by designer, Jake Knapp.

The MVP - Minimum Viable Product

A lot of the literature that you’ll encounter in the Product Management world revolves around developing Minimum Viable Products and releasing them into the world to see if the product is able to find Product–Market Fit. One of the most referenced startup posts of all time comes from Marc Andreeson, former CTO of Netscape, entitled The only thing that matters.

Andreeson’s post provides an excellent overview, but we also like these posts: Making sense of MVP and What does “Minimum Viable Product” actually mean, anyway?, which break out the idea a little further. It’s also worth checking out The Ultimate Guide to MVP from Hackernoon, which breaks out a bunch of helpful tools for building and monitoring an MVP.

If you’re a working at a startup that’s building or iterating on an MVP, we’d also recommend checking out the wealth of resources available to you in the YCombinator Library. YCombinator is a startup incubator that’s probably helped launch more successful technology companies than any other entity in the world.

You should also buy Eric Reis’s The Lean Startup immediately. It’s the seminal book on product development at a startup. It also provides some great insights about how Product Managers at existing companies should approach experimentation.

For an overview of MVP in audio form, check out the Startup Podcast:

VI. Defining the Product

There a number of schools of thought when it comes to the Product Requirements Document or “PRD” or “Spec.” Check out this Quora thread, What should a lean startup functional spec / product requirements doc look like?, for a peek into what this debate looks like. Basically, there are two sides to the argument. The buttoned-up view is that, as Product Managers, we ought to know exactly where we’re going, with a comprehensive PRD. The dissenting view subscribes to the notion that, in a “lean” world, PRDs tend to “overengineer” a solution in advance of testing; what happens if we invest a lot of money in building out our product based on a comprehensive PRD only to discover upon testing that a key element in the interface turns users off? Clearly that’s a concern worth thinking about, but we still think that there’s a lot of value in thinking through the PRD and that Great Product Managers Obsess over Documentation. As Jeff Bezos says, “There is no way to write a six-page, narratively structured memo and not have clear thinking.”

PRD Format

The Silicon Valley Product Group does a nice job summarizing what a PRD is in their How to Write a Good PRD. They say “The purpose of the product requirements document (PRD) or product spec is to clearly and unambiguously articulate the product’s purpose, features, functionality, and behavior. The product team will use this specification to actually build and test the product, so it needs to be complete enough to provide them the information they need to do their jobs. If the PRD is done well, it still might not be a successful product, but it is certain that if the PRD is not done well, it is nearly impossible for a good product to result.” Ultimately, this is the document that your development team is going to refer to when they actually build the product.

The process of writing the PRD can be – and really ought to be – a useful thought exercise, requiring that the author consider product planning with systematic thoroughness. The blog post How you write Product Specs is how you build products explains why.

As far as the actual structure of a PRD, we’ve found a few examples that are worth looking at. Check out: On Writing Specs and Asana’s Spec Template & Spec Training

Creating Alignment

If you work an existing company, chances are that even a brilliantly thorough and compelling spec will not be enough to win top-level approval of the product that you’re seeking to build. You will likely need to take the extra step of recruiting others to buy-in to your vision. As a Product Manager, you will want to focus first and foremost on data, making sure your decisions are supported reliably. But even that may not be enough. To get others to buy-in, you’ll also want to understand the art of storytelling. Check out Anna Marie Clifton’s talk at Mind the Product here:

For some other simple ideas on getting buy-in for your product, check out The Product Manager’s Guide to Getting Buy-In. Some of these ideas are further fleshed out in Mind the Product’s Top Tips for Negotiating With Stakeholders

We also really like this podcast from First Round, where Google / Reddit / Pinterest Product Manager Tyler Odean gets into the science behind influence and how that science can be used:

For a deep dive on creating alignment, you may want to check out the book Getting to Yes.

VII. Managing the Build

The Product Manager’s relationships with the Engineers and Designers responsible for building the product or feature will vary from company to company. Ideally, the entire Product team has been involved in the process of defining the problem and designing the solution. That’s how it works at many startups and early stage companies (in part because there are so few employees that differentiation of functions is limited). At later-stage companies, it’s more likely that you’ll find a Project Management or Agile Coach function that exists separately from Product Management, exerting influence for efficiency and timeliness in the building process (Project Manager to Product Manager: “I’d really love to help you with that, but we have to ship.”)

The next section will give you a feel for the different types of development teams commonly deployed to get products built. We’ll also talk a bit about how much tech and how much design you need to know to effectively interface with design and development teams. If you lack experience in this area, we encourage you to read on, because managers can set themselves back significantly when they get off on the wrong foot with a capable team.

Cross-functional Teams

No matter how you or your company chooses to structure your development team, it’s important to understand the basics of how to organize and motivate cross-functional teams (and nearly all development teams in the tech space will be cross-functional). In regard to this topic, we love the talk by Ron Lichty, developer management expert, talk entitled ‘How to Get Your Development Team to Love You,’ which you can watch here:

We also like this presentation by Ken Norton entitled Leading Cross-functional Teams (hint: bring the doughnuts). Jackie Bavaro focuses more on specifics around focusing on goals, clarifying the decision maker, and knowing when to escalate in her post Stakeholder Management: How I get Everyone on the Same Page. First Round also has a podcast episode that talks specifically about motivation here:

If you’d like to go deep on this topic, we’d recommend picking up Fred Brooks’s The Mythical Man-Month which you’ll often see referenced as the go-to material for explaining the human elements of software engineering.

Types of Development

Aside from what language your engineers are actually coding in, there are a number of different development methodologies that engineering teams employ to work efficiently and stay organized. Rather than go through each in painstaking detail, we’re going to recommend some broad overviews and then walk you through the chronology of how each methodology was created and developed, which will give you a better understanding of how they all relate to each other and which one you might ultimately want to choose – should you be responsible for making that decision.

We really like Roadmunk’s 8 Popular Software Development Methodologies because it includes some pros and cons that one might want to consider for each approach. We also like this visual guide from Toggl, which walks you through a few of the options in cartoon form (fun!). For a drier, but more descriptive explanation, methodologies, see the IT Development Portal’s Software Development Methodologies.

For a sense for where we’re going here, check out:

Waterfall

There are references to sequential or “waterfall” development that date back to the 50s, but the first formal description of this type of development is credited to Winston Royce, an American computer scientist who was heavily involved in early space missions, in his paper Managing the Development of Large Software Systems. We don’t expect you to actually read Royce’s paper, but you want to be aware that waterfall may be a good option if scope is fixed (user’s requirements aren’t changing) or users don’t want to be / can’t be involved in the development process. For more comprehensive guidance, check out Smartsheet’s When to Choose Waterfall Project Management Over Agile.

Agile Methodologies

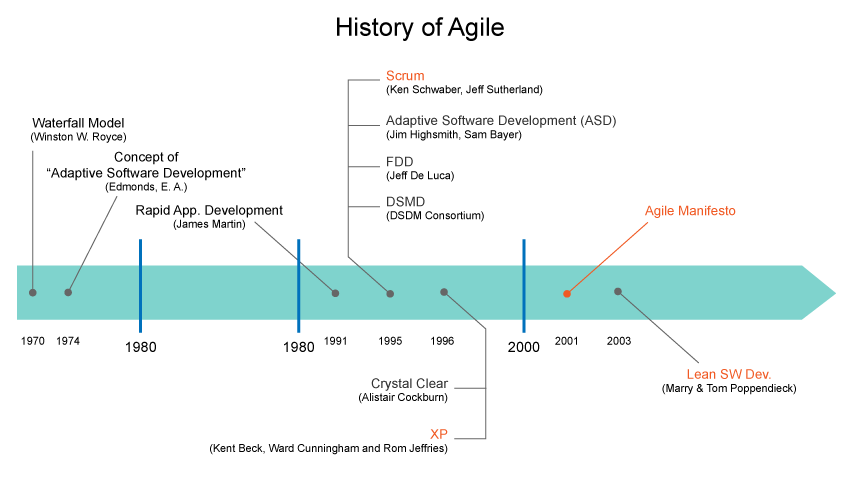

Realistically, the scope of software projects is very seldom stable. Even in situations where user feedback loops are not part of the process, internal factors (for example, an influential person changes his or her thinking) will create flux. Agile is flux-friendly. Development of this idea dates back to the 1970s. Agile focuses on adaptation to the challenges of the moment, while keeping the long term goal in view. Within this school of thought, a number of “lightweight” methodologies were developed, including Rapid Application Development (RAD, 1991), the Unified Process (UP, 1994), the Dynamic Systems Development Method (DSDM, 1994), Scrum (1995), Crystal Clear (1996) and Extreme Programming (XP, 1996).

All of these methodologies originated before the publication of the Agile Manifesto in 2001, but they are broadly categorized as agile methodologies. For a precise definition of what Agile is, we’d recommend reading the Agile Manifesto – its website evokes a simpler time on the internet, which we appreciate. We’d also recommend checking out Jacob Aliet Ondiek’s The 12 Agile Manifesto Principles Simply Explained, which provides a bit more context around what the principles mean. We recommend checking out The Agile Alliance for more tools and content around agile.

Scrum

The most common of the agile methodologies is probably Scrum. “Agile” itself is a set of principles without rules / guidelines for how to implement those principles. Scrum is a common set of rules for implementing agile principles. Here’s a peek into what Scrum is from Scrum.org:

We’d recommend taking a deep dive on Scrum.org’s What is Scrum? for more information on how Scrum is organized. We also like Eric Weiss’s You’re Doing Scrum Wrong and Here’s How to Fix It for an updated take on how Scrum can be used at modern companies.

Lean

The last of the agile methodologies we’re going to mention here is Lean Software Development, which is based on the lean manufacturing principles developed at Toyota in the 1960s and 70s. For an overview of what Lean Software Development is, and how it differs from Agile, check out Hackernoon’s Lean for Software Developers.

We recommend checking out Mary Poppendieck, who has authored many books on the subject, in her talk on The Future of Software Engineering from GOTO Berlin 2016:

Technical and Design Skills

One myth about Product Management (which hopefully we’re beginning to dispel) is that you need a Computer Science degree to do these jobs. Many accomplished leaders in the tech field are not technical people. On the other hand, it is necessary that Product Managers have the ability to communicate with technical people effectively. Fred Wilson, cofounder of the VC firm Union Square Ventures, has an excellent post on this topic in his blog entitled The Yin and Yang of Product and Engineering which explains how the two functions should fit together at various stages of company development.

For a practical guide on what to do to gain technical experience, check out Lulu Cheng’s blog post Getting to “technical enough” as a product manager. Julie Zhuo also has an excellent post on this topic, where she approaches the question of How to Work with Engineers from a designer’s perspective. Ken Norton has a post called How to Work With Software Engineers that focuses more on the “soft skills” necessary to be effective here.

Looking at the communications challenges the other way around, we recommend Julie Zhuo’s post on How to Work with Designers. Justin Hileman of Dropbox has a similar post on the Dropbox blog that we love called On Working with Designers. First Round also has an excellent blog post talking about a major design idea (minimizing friction) called Amazon’s Friction-Killing Tactics To Make Products More Seamless which you may find to be helpful.

If your background is business-oriented or technical, you will want to take special care to understand the pivotal importance of good design in producing successful products. We recommend picking up either The Design of Everyday Things or Don’t Make Me Think

VIII. Releasing the Product

Anyone who has seen Field of Dreams (or Wayne’s World 2) will recognize the quote “if you build it, they will come.” As a Product Manager, you’ve now overseen the conception and building of your product. Now, you need to make sure customers are using it – and using it in the ways you anticipated. Generally speaking, this is done with alpha and beta tests, which release products to small groups of users before releasing to a broader base. Beyond these tests, you’ll want to make sure your Marketing and Sales teams are equipped to talk about your product in a way that accurately represents the value you have built. Different companies will do product launches differently. Here, we’ll go over some of the main Product Manager touchpoints for a successful launch.

Alpha and Beta Tests

Alpha and beta tests are designed to achieve similar goals, but experiment on different audiences. Typically, alpha tests are performed by internal employees in some type of development or “sandbox” environment. Beta tests are performed by actual users and clients with the live or “production” version of the product.

For a step-by-step walkthrough of what a successful beta test looks like, check out Intercom’s How to run a successful beta in 7 steps. If you’re working at an early-stage company, Ula Holovko’s post, How to Conduct a Closed Beta Testing with Zero Budget might be helpful. In it, she goes through an actual case study.

You may also want to check out this Product Podcast on the subject of beta tests from Prachi Wadekar, Product Manager at Mixpanel:

The Launch

We have now reached the finish line (kind of)! It’s time to actually launch the product to users. Different companies will have different approaches here – particularly when you look across the entire B2B vs B2C space. We’ll point to a few resources that can help inform your thinking.

First, to get the nomenclature right, you’ll want to check out a series of posts outlining technical terms associated with releasing product in Turbine Labs’s Deploy != Release blog posts here and here.

Next, you might want to check out a “checklist” like the one Larry Kim published, Ultimate Product Launch Checklist. Kim does a pretty good job of outlining the many tasks you should be considering. First Round does an excellent job distilling their portfolio’s collective launch experiences down in their blog post The Simple Rules That Could Transform How You Launch Your Product. For a more specific look at that process from the perspective of Amazon, you’ll want to check out First Round’s My Launch Lessons from 37 Minutes in an Amazon War Room.

One of our favorite posts on product launches comes from the CEO of Slack, Stewart Butterfield. It’s the memo he sent his company before Slack’s launch, We Don’t Sell Saddles Here. This post covers a lot. It could have gone in the “company mission” section above or the “marketing” section below, but he sent it as part of their launch, so we’ll just leave it here.

Product Marketing and Sales

Generally speaking, Marketing and Sales teams are going to handle a lot of the work that goes into the launch. Sometimes, the Product Marketing Manager will handle the relationship with Sales and create many of the communications and collateral materials that the Sales Team will need in order to effectively sell the product. In this section, we’ll explain a bit about important functions within Marketing and Sales and how Product Managers should liaise with them.

At a technology company, it’s likely that the person most important to a successful launch is Product Marketing Manager. We like Yasmeen Turayhi’s blog post, When it’s time to hire a Product Marketing Manager, which explains what the role is and how it fits into a typical early-stage company. First Round has a similar post, ClassPass’ CMO on How and When to Invest in Product Marketing We also like the post Why Product Marketing is the Growth Secret Weapon You Absolutely Must Have from the Growth Marketing Conference, which expands on the difference between a general Marketing team and a Product Marketing team. For a look at what excellent Product Marketing looks like at some big name tech companies, check out the post What I Learned From Developing Branding for Airbnb, Dropbox and Thumbtack.

To better understand how to liaise with the Sales Team, read the post How Product Management Can Work Effectively with Sales from the Uservoice blog. You may also want to check out The Product Manager – Sales Team Disconnect, which goes into potential areas of friction and what to watch out for. To better understand what great salespeople do, check out Andy Raskin’s The Greatest Sales Deck I’ve Ever Seen.

If you want to develop an excellent understanding of how Product, Sales, and Marketing fit together to drive growth at a startup or existing company, we’d recommend picking up the book The Four Steps to the Epiphany by Steve Blank. It’s one of our favorite books for explaining how to “build the machine” of a business.

IX. Advanced: Building a Product Team

If you’re extremely lucky, you’ll find yourself at a startup that needs to build out a Product team or at an established company that asks you to assist in hiring a team. Either way, you should have some idea of how to structure a Product Team and how to hire Product Managers. An excellent overview of how to build high-functioning teams (in Product specifically) comes from Martin Eriksson in his “Building a Kick-Ass Product Team” talk:

On designing the Product function, you should check out First Round’s To Build Great Products, Build This Strong, Scalable System First and The Power of the Elastic Product Team — Airbnb’s First PM on How to Build Your Own. On the team design, check out Mind the Product’s Why you Should Organize Product Teams Around Customer Experiences.

On the hiring side, we like Jackie Bavaro’s How to Hire Great Product Managers. Jackie also wrote an excellent book on the Product Management interview process entitled Cracking the PM Interview that will definitely be helpful if you’re sitting on the “interviewee” side of the table. You should also check out First Round’s podcast Find, Vet and Close the Best Product Managers:

X. Helpful Resources and Citations

Here are some of the books and blogs worth following that contributed heavily to this outline that may not have been mentioned above:

- <a href="https://www.amazon.com/Lean-Product-Playbook-Innovate-Products/dp/1118960874”> The Lean Product Playbook </a> by <a href="https://twitter.com/danolsen”> Dan Olsen </a>) (probably the most thorough book on customer-driven Product Management)

- <a href="https://www.productschool.com/the-product-book/”> The Product Book </a>) by Product School

- <a href=“https://www.intercom.com/books/product-management”>Intercom on Product Management</a>

- <a href=“https://svpg.com/”> Silicon Valley Product Group</a>

- <a href=“https://firstround.com/review/product/”> The First Round Review’s Product Magazine </a>

- <a href=“https://amplitude.com/blog”> The Amplitude Product Blog </a>

- <a href=“https://www.pendo.io/pendo-blog/”>The Pendo Product Blog </a>

- <a href=“https://twitter.com/sebastienphl”> Sebastien Phlix’s</a> <a href=“https://medium.com/@sebastienphl/my-product-management-reading-list-2017-cb874975c635”>2017</a> and <a href=“https://medium.com/@sebastienphl/my-product-management-reading-list-2018-bad70780c51f”>2018</a> Product Management Reading Lists

- Also check out Product Coalition’s <a href=“https://productcoalition.com/a-comprehensive-list-of-product-management-courses-522ad0b96b75”>List of Product Management Courses</a> if you’d like to continue your education!